Weekly Dose: aspirin, the pain and fever reliever that prevents heart attacks, strokes and maybe cancer

Andrew Tonkin, Monash University

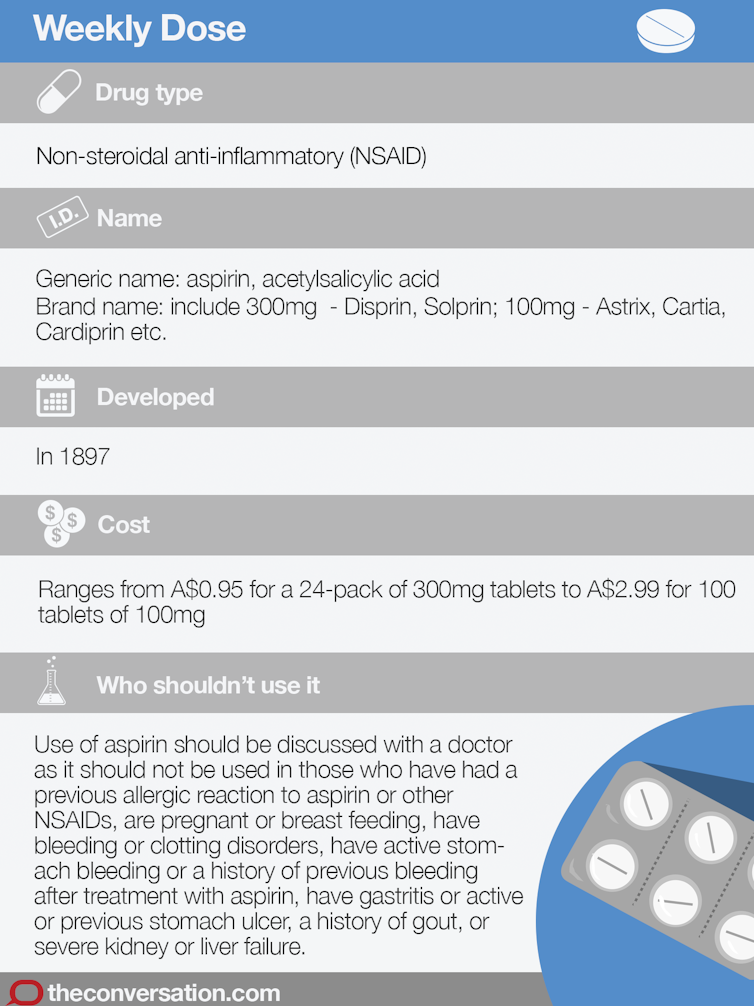

Aspirin is, like ibuprofen and Voltaren (diclofenac), a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to treat pain and reduce fever.

What makes aspirin different from other NSAIDs is its ability to thin the blood, and it is used to prevent blood clotting in those at risk of heart disease and stroke. Recently, it has also shown potential to reduce the risk of some cancers.

How does it work?

Aspirin works by inhibiting an enzyme called cyclooxygenase, which generates prostaglandins. These are in turn associated with inflammation, pain and fever.

Through the same enzyme, aspirin also inhibits the production of substances called thromboxanes. These are responsible for the aggregation of platelets in the blood, a process needed to stop bleeding. This is what we mean when we say aspirin “thins the blood.”

The mechanism whereby aspirin might be protective against cancer is not fully understood but certain genetic and other characteristics may identify those who might particularly benefit.

History

In the 16th century BC, Egyptians documented on papyrus that the bark and leaves of willow and related plants had pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory properties. The Greek physician Hippocrates later noted these same properties in the 5th century BC.

Aspirin’s more recent history came from purifying salicylate, the active component in ancient preparations. In 1897, this culminated in the development of acetylsalicylic acid or aspirin.

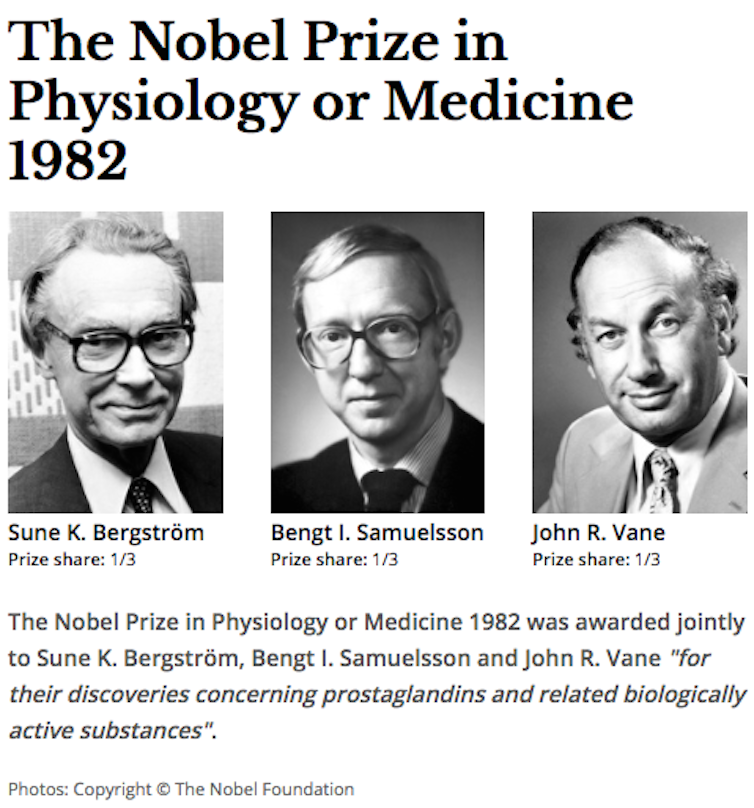

Today’s interest in aspirin stems largely from the seminal 1971 publication by English pharmacologists John Vane and Priscilla Piper, who discovered its action in inhibiting prostaglandin production. In 1982, Vane shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in this area.

In 1950, an American general practitioner Lawrence Craven noted that patients who had their tonsils removed and chewed Aspergum (a gum containing Aspirin) experienced severe bleeding. He later said daily aspirin appeared to prevent heart attacks in his patients.

Craven’s claims were doubted by fellow doctors because they were not the subject of randomised trials. This was around the time that the importance of blood clots in events such as heart attack was recognised, and methodology that informed the robust design and interpretation of very large clinical trials was developed.

These trials included aspirin among the first therapies tested. A recent overview of such trials showed that aspirin, when compared to inactive placebos, reduced serious vascular events such as heart attack and stroke by about 12% in those who had not previously had such conditions, and by about a fifth in those who had experienced them.

However, the overview also confirmed that benefits came at the cost of severe bleeding (due to aspirin’s ability to prevent clotting) from the stomach and bowel, or resulted in bleeding into the brain.

It is now apparent that factors such as advancing age, smoking and diabetes increase not only the risk of heart attack and stroke, but also major bleeding. This means aspirin can’t be prescribed indiscriminately for everyone.

Aspirin and cancer

In 1988, Melbourne surgeon Gabriel Kune reported that aspirin was associated with lower rates of bowel cancer.

Subsequently, trials supported reduced cancer rate and death in those taking aspirin, not only of the bowel but also of some other organ types. However, cancer was not specified as a major outcome of interest at the beginning of these studies, and because of this, was not examined rigorously.

How is it used?

Australian guidelines for the use of low-dose aspirin to prevent heart events and stroke are clear cut. If aspirin does not cause problems, such as severe bleeding, it should be used life-long in everyone who has experienced heart-related events such as angina, heart attack, coronary bypass surgery and stroke.

In those who haven’t experienced these, decisions on aspirin use must be based on weighing up individual risk of bleeding and these events occurring in the future.

The latest, authoritative recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force about prevention of cardiovascular disease and bowel cancer state that for those aged 50 to 69, taking aspirin depends on the estimated risk of events that might be prevented, and also of bleeding and life expectancy.

In those aged less than 50, or 70 years or over, there is insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of initiating aspirin use.

Present Australian guidelines for the prevention of bowel cancer state there is insufficient evidence to recommend aspirin for all people at average risk, and emphasise that diet and lifestyle improvements, as well as screening, are effective in reducing risk.

However, those with a strong family history of bowel cancer should often be referred for specialist assessment and aspirin might be recommended after genetic testing.

The low dose of aspirin typically used is 100mg daily. This is much less than that which might relieve a headache, other pain or fever, and for which paracetamol is generally recommended in the first instance.

Who shouldn’t use it?

Use of aspirin should be discussed with a doctor as it should not be used in those who have had a previous allergic reaction to aspirin or other NSAIDs, are pregnant or breastfeeding, have bleeding or clotting disorders, active stomach bleeding or a history of previous bleeding after treatment with aspirin, gastritis or an active or previous stomach ulcer, a history of gout, or severe kidney or liver failure.

Aspirin should be taken with water, with or without food. Taking an enteric-coated tablet, which is designed to prevent the aspirin from being released in the stomach, decreases the chance of an upset stomach.

How much does it cost?

Aspirin is relatively cheap and the cost can range from A$0.95 for a 24-pack of 300mg tablets to A$2.99 for 100 tablets of 100mg.

Other points of interest

The ongoing ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial, conceived and initiated in Australia, has completed recruitment and is following up more than 16,700 healthy Australians aged 70 years and over, and almost 2,500 people in the United States. It involves more than 2,000 Australian general practitioners as co-investigators.

The primary question investigated is whether aspirin improves healthy active life years (time lived free of dementia or physical disability), outcomes fundamentally important to the elderly. This encapsulates the net effect of benefits and risks of aspirin.

The trial will also provide unique data concerning whether aspirin prevents cancer in the elderly. It is anticipated that ASPREE’s findings will be reported in 2018.

Andrew Tonkin, Professor and Head, Cardiovascular Research Unit, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Andrew Tonkin is a senior investigator to the ASPREE project.